For the past two years, our club has been working closely with a local FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) team, Team 6496. We, Vincent Wang and Maverick Chung, have been mentoring and supporting the high school team since our freshman year, teaching them a variety of engineering-related skills by helping with the construction and design process.

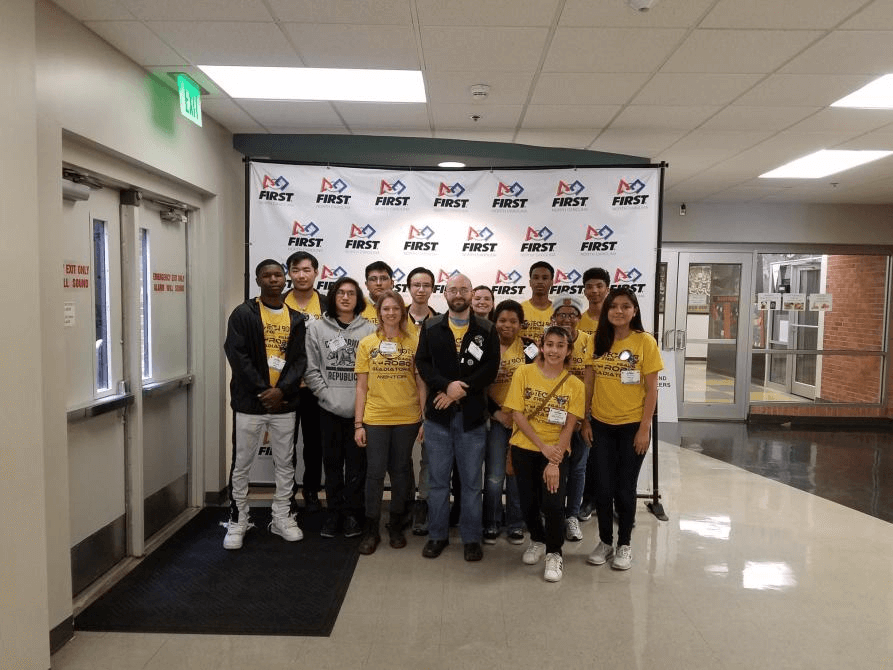

Above: Team 6426 after making the competition finals in Spring 2019 (full size image)

2018-2019: Bringing our A-game in our first year

In 2018-2019, the team was Team 6426: Robo Gladiators, sponsored by Compass Youth Center.

We were initially introduced to the fledgling team in Fall of 2018, the start of the FIRST Deep Space season. At the time, the club was relatively new, with only a few years of experience working mainly out of a high school club room, their rookie year being in 2017. Our robotics team members, along with the lead mentor, Duke graduate student Chelsea Shoben, managed to secure a room in the Duke Foundry, a professional makerspace where our Duke Robotics Club is also housed, as well as expert mentorship from an FRC veteran-turned Duke professor, Professor in Electrical Engineering Tyler Bletsch.

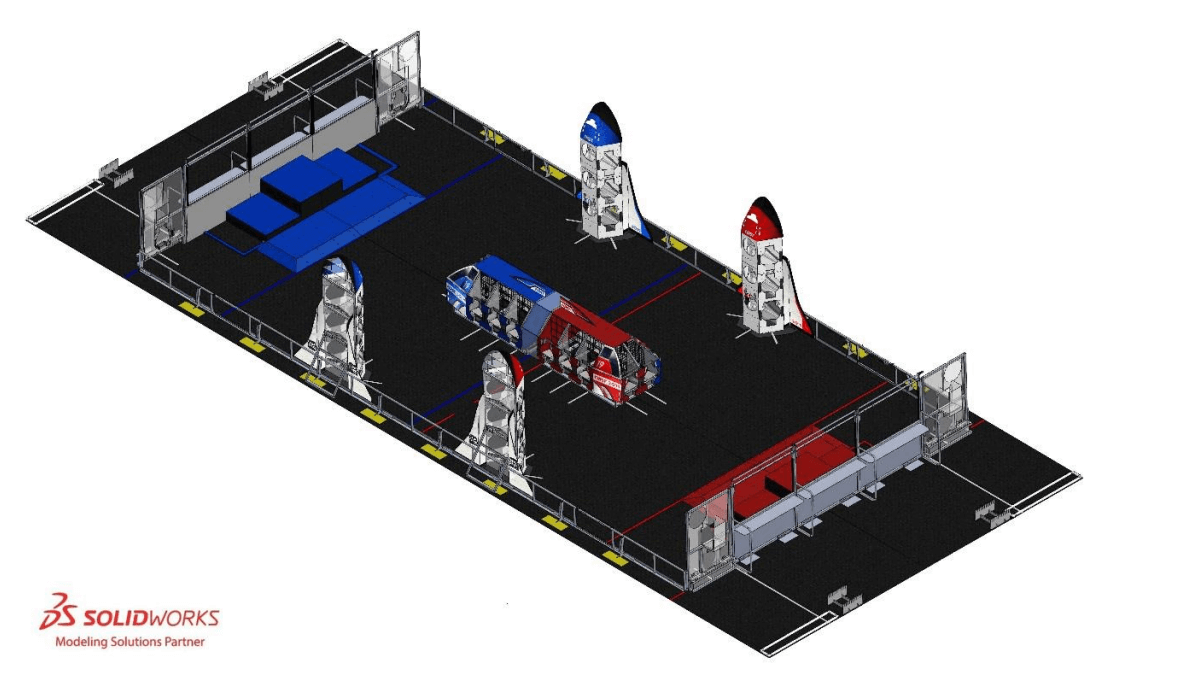

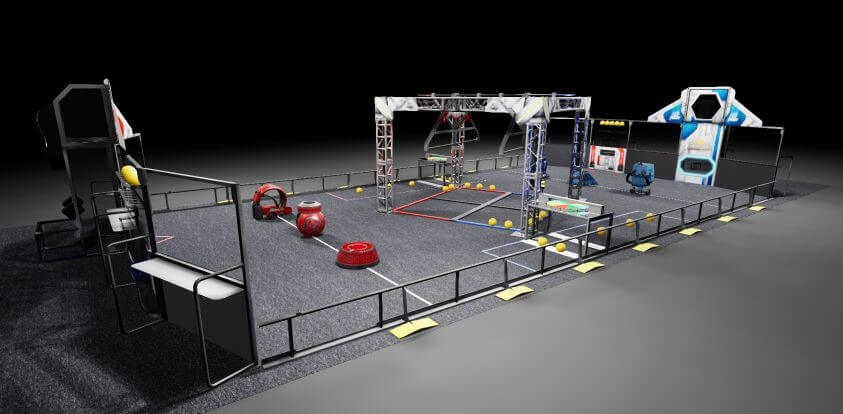

For those of you unfamiliar with FRC, it is a significant step up from the much smaller FIRST Tech Challenge (FTC) competition, which consists of ~18 x 18 x 18 inch robots competing in a small play environment. FRC is much larger, involving robots roughly 2.5 x 2.5 x 5 feet with weight up to 120 pounds. They play on fields the size of basketball courts, often performing tasks such as rapid-fire ball launching, or climbing high above the ground. Teams have from January until the start of competition in March to prototype, test, and build their robots. Last year, the game was space-themed, involving loading cargo into rockets and cargo ships while securing them with hatches and preparing for lift-off. In more technical terms, it involved collecting a variety of balls and flat panels, storing them in buckets of varying heights, and then climbing up a high vertical incline.

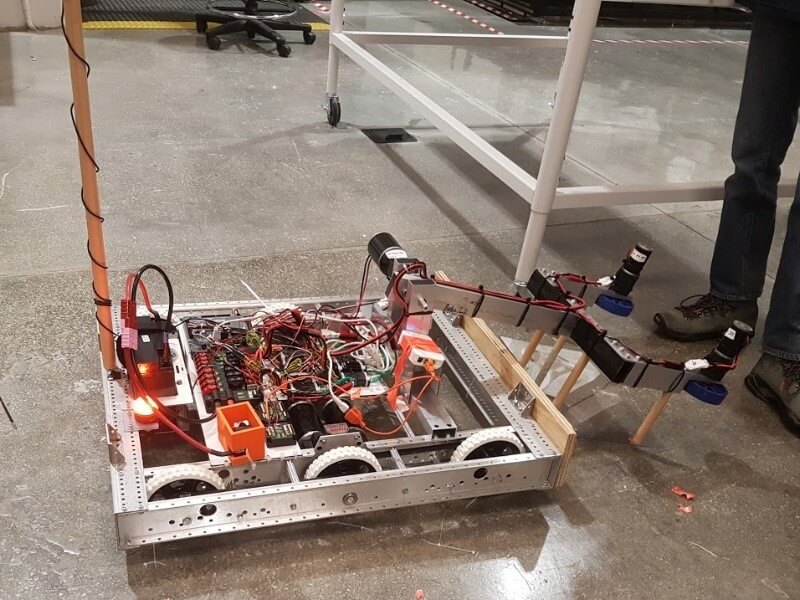

We started out by getting the students to work right away, building a mockup of the field out of 2x4s and plywood, while also beginning prototyping, testing our intake ideas with wheels hacked onto drills. We worked alongside the other mentors to show the students the entire engineering design process, from the brainstorming and ranking of ideas, to the first prototype, to testing and retesting again. We taught skills from Computer-Aided Design (CAD) using OnShape to rapid wood prototyping to final metal fabrication, with a particularly emphasis on safety since it was many of the students’ first time using heavy machinery. Because of our limited time, all of the CAD was nothing more than 2D sketches, mostly for planning out an arm mechanism and to ensure the spacing and lengths would fit well together.

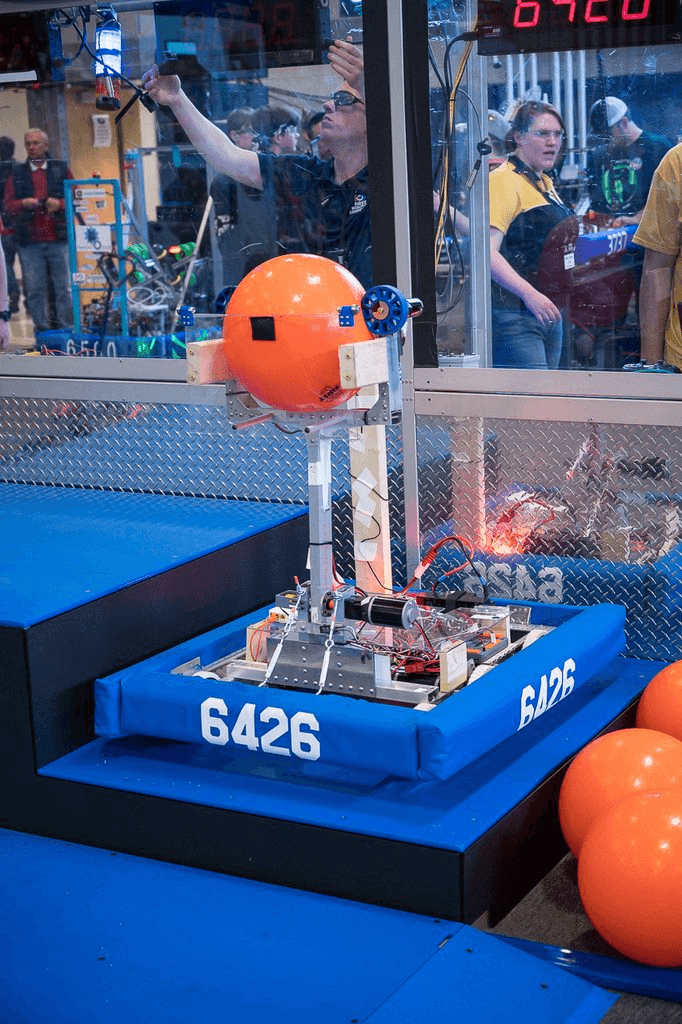

The first build of the robot took roughly 4 weeks. Once all the kinks were ironed out and the first iteration of the bot was complete, the robot was ready for testing. Professor Bletsch took the controls to demonstrate how to troubleshoot a bot that had just been brought into existence, mentioning several times not to trust the controls to do what you thought they would do. A couple minutes later, he introduced the team to their first catastrophic failure by accidentally smashing the intake into the ground, inadvertently presenting a perfect chance for the mentors to introduce the failure analysis and iterative design process sections of the engineering design process. A few iterations later though (and one new arm later), and we had a successfully working robot, ready for competition season in the Spring.

At our first competition, the event was crazy. You could feel the energy in the air – the entire venue hummed with the vitality of all the robots and teams and students working frantically to succeed. The team already had experience competing at the smaller FTC competitions, but we spent quite a bit of time with the students planning things like pit organization and preparing for the robot inspection. Despite a rocky start—the team’s robot managed to rip its arm in half during the team’s second competition—the team recovered quickly and efficiently. We didn’t make it to the playoffs during our first competition, but we ended up as the highest ranked team that was not picked to play in the final bracket, and we resolved to do better at our next tournament.

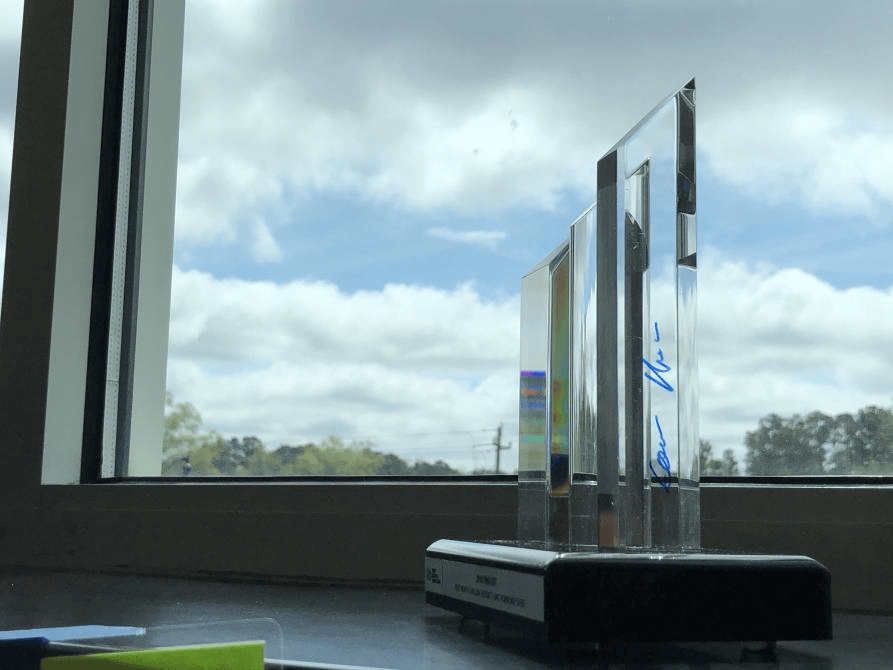

By the time the second competition rolled around, we were ready to take on the world. We played through all our qualification matched and by the end, we were once again the highest unpicked team, which meant that we were a backup. So, if a robot died during the playoff bracket, we would replace them. We sat in the stands, watching the quarterfinals, then the semifinals, when a frantic student rushed up to us. Their robot had died, and they needed a replacement in the next match. Our robot was called to the field immediately. We ended up playing the match with the finalist team, working at playing defense and put up a hard fight to prevent the other team from scoring. We lost that match, but we were happy regardless. Our first-year team was in the finals! Professor Bletsch remarked at the beginning of the award ceremony that “if you had caught [him] at the beginning of finals, [he] would have bet [his] car that we didn’t make it.”

Overall, our first competition year was one of the most exciting we’ve ever participated in, and we were able to help the team grow from a small club working on mini FTC-sized bots, to using heavy machinery and design concepts to create a fully functional robot, fit for a competition of the scale that FRC offers.

2019-2020: Taking it to the next level

In 2019-2020, the team was Team 6496: Area 27.

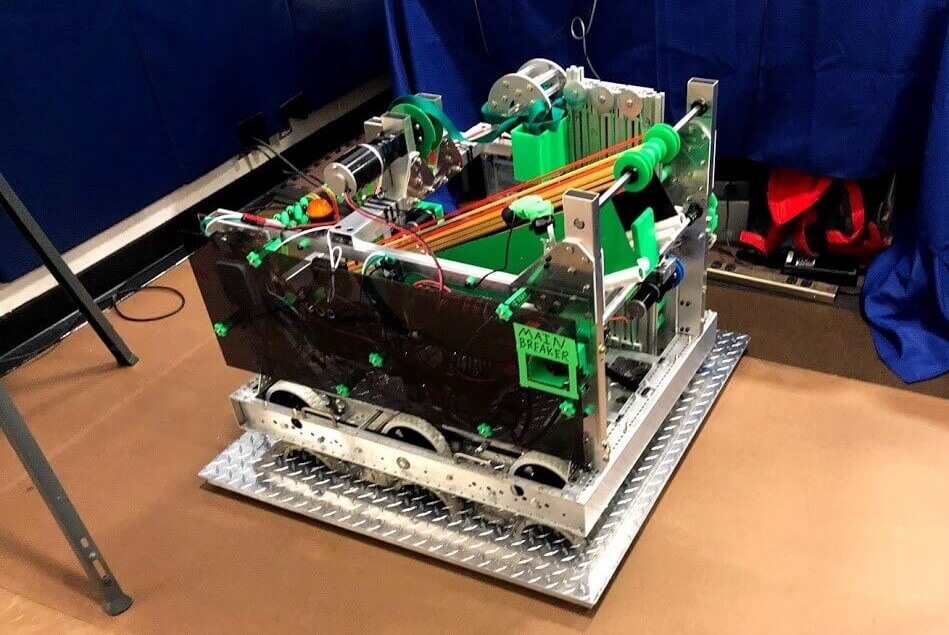

This year, our competition season went much more smoothly. With a full year of FRC experience under their belt, our team was ready to go full steam ahead from the beginning. We started out the season helping the students with additional machine and concept training, this time working with former FRC team members from Professor Bletsch’s old team, the Terrorbytes, who worked with us to help teach coding and controls. While we trained some of the students on additional machining, such as the laser cutters and bandsaw tools, and on the use of “true” 3D CAD, the Terrorbyte members worked to get the programming team up to speed on Java practices and the RoboRio wiring system used on the robot. While we weren’t teaching CAD, we even learned quite a bit about the FRC controls system, as well as the specialized WPILib library used to control the robot. During the semester, we finally managed to set up a true CAD team as well! With the enthusiasm of some of the students, a few mentors got together to teach a couple of the students 3D CAD design using SolidWorks, allowing us to finally begin modeling our robot in earnest for the first time. By the midseason, the students had put together a full model of the robot in SolidWorks, which is pretty impressive for a first-semester CAD team!

We also spent copious amounts of time on recruitment for the new club, putting together introductory meetings to entice new members. We managed to retain 6 new members for the 2019-2020 season, boosting our membership by almost 200%. With new skills under our belts and new members eager to get started, we started off the 2020 build season in January with a bang!

When Spring came around, the build season once again began in earnest. This year, the competition revolved around a Star Wars themed challenge, requiring robots to shoot kickballs into one of three goals, before climbing a tall hanging device in the middle of the field to “prepare the shield generator”. Using the new skills that they picked up the previous semester, the team quickly went to work on using the knowledge from the past year to create their new robot design. Using a belt-pulley system with 3D printed pulleys, the robot was capable of quickly scooping up as many as five balls at a time in order to deposit them into the low goal, which was both quick and accurate. The team also created a hanging mechanism using a series of cascading 80/20 bars, which lifted an aluminum hook up into the air before retracting the hook using a winch system. We managed to incorporate many new techniques learned by the students, from waterjet-cutting the hook parts at Duke’s Innovation Co-Lab to custom code modifications.

This year, our first competition was miles ahead of where we were last year. With quick, accurate shooting using our conveyor, as well as our reliable hanging arm, we managed to secure a position in 13th place out of 29 competitors, placing us well within the range of playing in the playoff matches. In fact, after the teams were picked, we ended up in 9th place, one off from being able to play as a team captain, selecting our own alliance partners. We ultimately joined alliance number 7 alongside team captain 435, the Robodogs, as well as our partner team 6908, Infuzed. We finished strong, making it all the way to the semi-finals before being knocked out. Overall, the competition was our best showing yet, and we even won the Gracious Professionalism Award for our performance during the competition!

Sadly, the rest of the season was cancelled due to concerns surrounding the coronavirus pandemic, but this team of high school students has been one of the best group of thinkers and designers we’ve ever had a chance to work with. They took every challenge thrown at them and stepped up to the plate. We can’t wait for next season to work with this fantastic group of engineers again, and we can only begin to imagine what they’ll do beyond high school robotics.

This post was co-authored by Vincent Wang and Maverick Chung.